Living On This Land

& Learning

I grew up on land as rich in gold as it was in death. I would not come to know this until I was much older. As a child, the Yuba River was a second home to me. My family spent entire days on shining beaches, sunning ourselves on hot granite rocks, by the cool waters. Occasionally, I would catch a person panning for gold in the shallow waters, completely absorbed in their reverie. My child self, found this perplexing, that someone could be so committed and absorbed in searching for small flakes of gold with all the glorious nature around to explore. Wandering the trails above the winding veins of the Yuba, rock-hopping up or down river was a favorite pass time for friends and I, scrambling like monkeys. Never truly contemplating the occasional grinding hole we came across. The holes were useful for crushing up paint stones, a clay base rock solid and acting as a palette for mixing colors that we would paint ourselves and the neighboring rocks with. But who left these ancient imprints in the stone?

Over a coffee, many years later I had my first talk with a woman named Shelly Covert. I had reached out to her because I wanted to learn more about the indigenous people of Nevada County. As the tribal council spokesperson for the Nisenan she shared with me the history of her people. This first encounter, became a three-hour long conversation, in which I learned the devastating effects of the Gold Rush on the original peoples of the area. Prior to 1850, approximately 7000 first nations people were living here. After the first two years of the Gold Rush, it is estimated that half of that population was gone. This devastation was due to outright massacre and the disease brought here by gold miners. The atrocities committed in what is now call Nevada County are truly unspeakable. Today there are only 147 recognized members of the Nisenan tribe. I also learned from Shelly the origin of the name of my beloved Yuba. “Uba,” she says. “Uuuuba,” I try. The only Nisenan word that remains on the landscape.

I wonder now if this river recognizes itself. Its shape has been changed from the 1850s, diverted many times since then. The land is different too, blasted by hydraulic cannons. Areas of Nevada County called the "Diggins," mark the graveyard of forests. Where the land is but a carcass of what it once was, bleached white, desolate scars on the hills, where greed stripped away the natural beauty. Proof of the ways that commercial and industrial desires can shift the landscape. Despite the destruction and violence of the Gold Rush, some survived the devastating clear cutting, mining and genocide of the past.

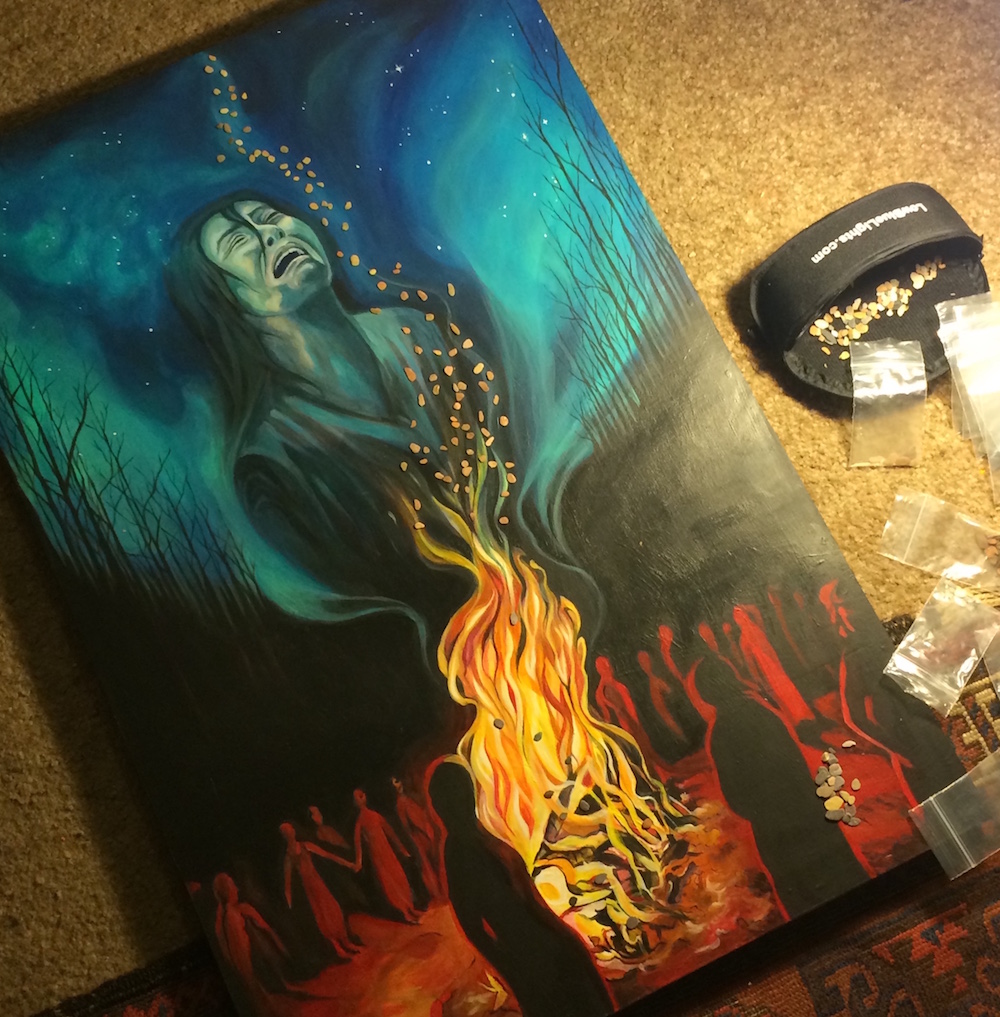

Shelly's and my conversation inspired a collaborative art project which included local artists creating pieces for the Art Reception before Nisenan Heritage Day. The goal being to involve community members in awareness and dialogue utilizing the thought-provoking medium of art. Below is my piece, which incorporated small river stones as a way to evoke the deep connection the Nisenan hold to this place.

“The Nisenan people were a cremating society. Their ancient ritual of burning the dead dates back thousands of years and countless generations. Steeped in protocol and social design were the means to burn the departed and all their belongings, to cry and mourn their death and to honor their remaining family members. Then, the spirit released, would travel to the sacred mountain where the first spirit food was eaten. Finally, the spirit would travel on to the Milky Way. After the Nisenan were forcibly removed and their lands taken from them, the colonizing settlers outlawed burning of the deceased.” –Shelly Covert

Today the Nisenan do not own the sacred land where these rituals took place. Their burning grounds would hardly be recognized by conventional colonial standards. A cleared patch of unmarked forest with no markers or clear definitions. This was a place of ritual, of mourning the passing of a loved one and of truly honoring loss.

Since my first meeting with shelly my relationship to this place has changed. When I walk by the river, I wonder who fished here long ago. When I come to a grinding stone, I wonder who was here preparing a meal for their family a mere hundred years ago. When I walk in the woods and come to a clear space, I wonder on what sacred sites I may tread. Is this a place of ritual? Of mourning? When I pass a gold mining monument, there is no sense of historic pride in me, I only feel a legacy of destruction, pain, and loss. The monument has become a tombstone in my mind.